Introduction

As we have seen in the “method” section, most of the time, the folk elements are mere byproducts of his being exposed constantly to folk music when he was younger and his nationalism. His music is generally said by critics and composers such as Cui, Mussorgsky, Bülow, and acknowledged by him, as having a “folky” style rather than directly incorporating folk melodies, except when the music is about folk music, like his 2nd symphony, 50 Russian folk songs, etc.

What will be looked at first in this section are some tunes that directly and play important parts in his music and their musical characteristics, and then in the subsequent section, native tunes from places he frequented. In the last section we’ll be bringing all information from this research together to help us analyze Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto and see what can be done to realize the goal of this research.

Tchaikovsky's Concert Music

The theme of western music often has inner dialogues between inner lines, both melodically and harmonically, creating tensions and resolutions. As certain aspects of a piece become more complex, other parts are molded to complement that change. However, in a strict Russian school, this does not happen. Often, in symphonic music composed by those of Russian schools such as Cui, Glinka, Borodin, etc. do not follow this pattern. The entire motivic and harmonic development rely on the structure of the implemented folk tune, in other words, the parts are now not dependent on each other, but entirely on the contour of the main melody. This causes music to repeat itself without clear musical direction. (D. Brown, 1978)

In Tchaikovsky’s second symphony, instead of following the traditional Russian school principal, Tchaikovsky opted for a more western approach, playing around, changing and transposing the melody, adding inner conversation between the lines.

The first part of the symphony begins with a slow introduction. Here, a solo horn plays the Ukrainian version of the famous Russian folk song “Down by the Mother Volga”, which kept its form throughout the exposition. The tune repeats a few times, with each time having a different harmonization and instrumentation. Sometimes, the melody stops altogether and breaks off into another completely different theme.

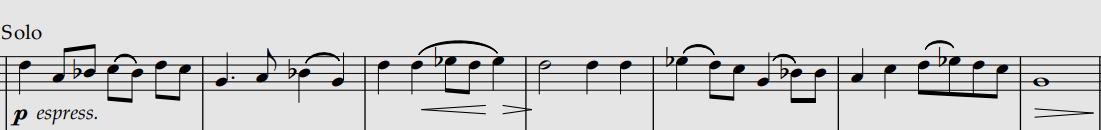

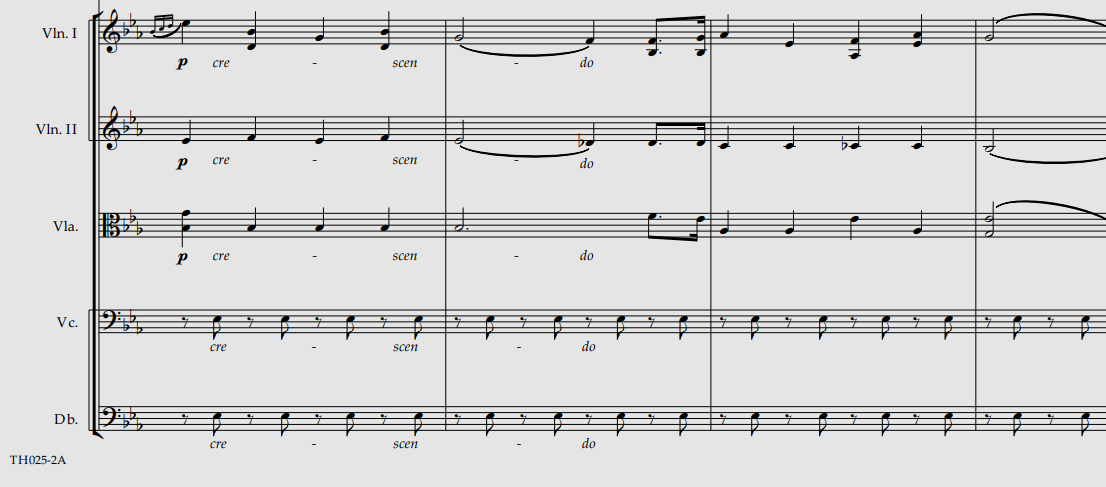

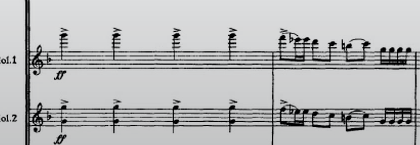

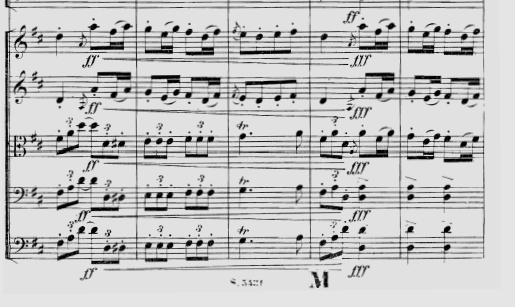

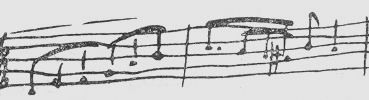

Opening theme of the 1st movement.

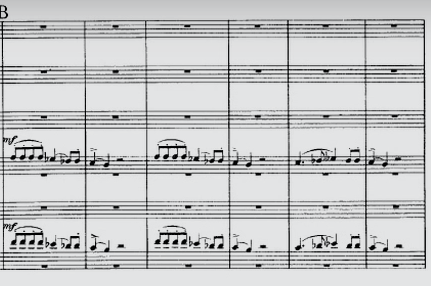

Opening theme of the 1st movement. The accompaniment for the 3rd measure of the theme later in the movement.

The accompaniment for the 3rd measure of the theme later in the movement.In the accompaniment, we find something quite interesting: the bassline moves in a melodic fashion, with the inner parts interacting, resolving itself in response to the tensions created by its neighbors. In German music, this would have seemed to be very normal, this harmonic movement is prevalent in music of those such as Brahns, Beethoven, and Bruch. However, for contemporary Russian composers of the century, this was much less common.

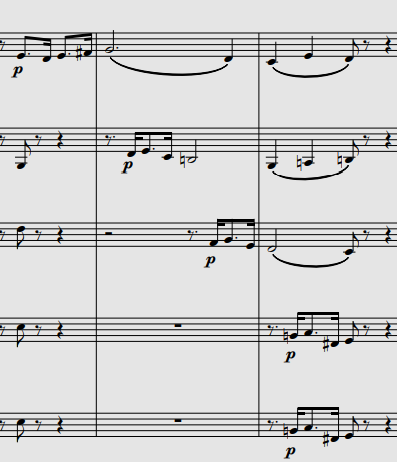

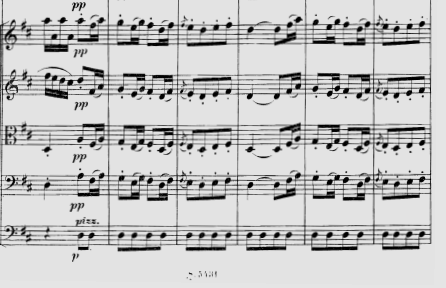

This can also be seen in his other implementation in the symphony. The second movement appears to us as a scene, the extreme sections of which are based on the scene of the wedding procession from the early opera “Undine” that was destroyed by the composer himself. And in the middle section the Russian folk song “Strands, my spinner” (Пряди, моя пряха) was introduced. While the melody remains unchanged, the harmony and embellishment are both colorful, exchanging lines back and forth and forming new background dialogues.

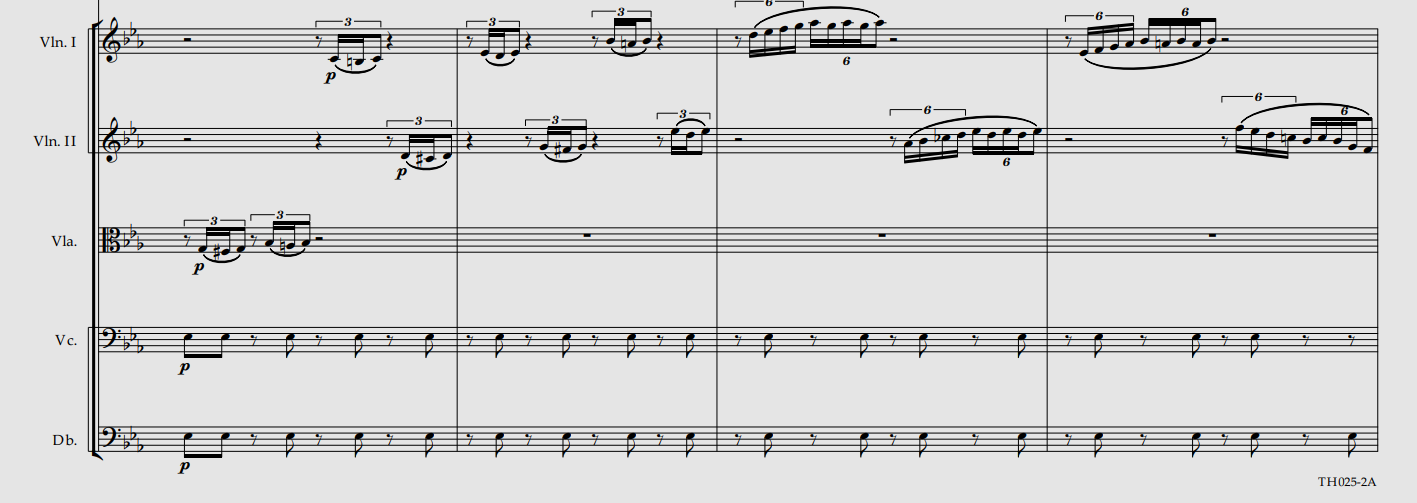

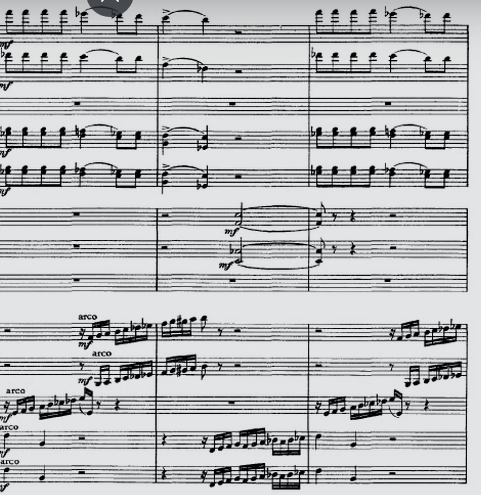

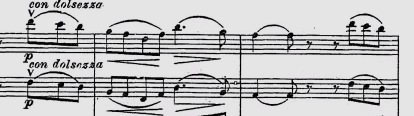

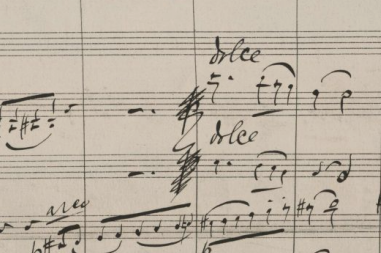

Embellishment I measure 109 - 112.

Embellishment I measure 109 - 112. Accompaniment I measure 109 - 112.

Accompaniment I measure 109 - 112. Embellishment II measure 113 - 116.

Embellishment II measure 113 - 116. Accompaniment II measure 113 - 116.

Accompaniment II measure 113 - 116.After repeating the themes quite a few times, the themes in Tchaikovsky’s music would see themselves slowly develop, following the traditional German thematic development. For example, in the part after the introduction of the folk theme in the second movement of his symphony, the rhythmic pattern of the folk tune was mimicked and by the succeeding melody(left) which would lead into further development and introduction of a new theme (right):

These Russian folk music originally have much simpler harmonies. For example, in minor keys, we would see i - iv - V very often. Tcahikovksy’s approach was a mix of the melody-dominant traditional Russian school: repeat the main theme a few times and change up the accompaniment; and western practice: develop the theme and harmonize such that the tensions and resolutions from the background help drive the music forward.

Tchaikovsky had always liked to travel, and on his trip, he would jot down every little idea he had along the way, be it on a piece of paper, or a bank note. (letter 778) This is also evidenced in his other letter he wrote to Nadezhda von Meck during his holiday in Italy (at the time of writing he was in Pisa) after his encounter with a young street singer:

“I do not remember any simple folk song ever having made such an impression upon me. This time the lad sang me a charming new melody (see the picture above), which I intend to make him sing again, so that I may write it down for my own use on some future occasion.” (letter 765)

Another well-known incorporation of folk music into his work is the inclusion of Во поле береза стояла (In the Field Stood a Birch Tree) as the secondary theme of the last movement of his 4th symphony.

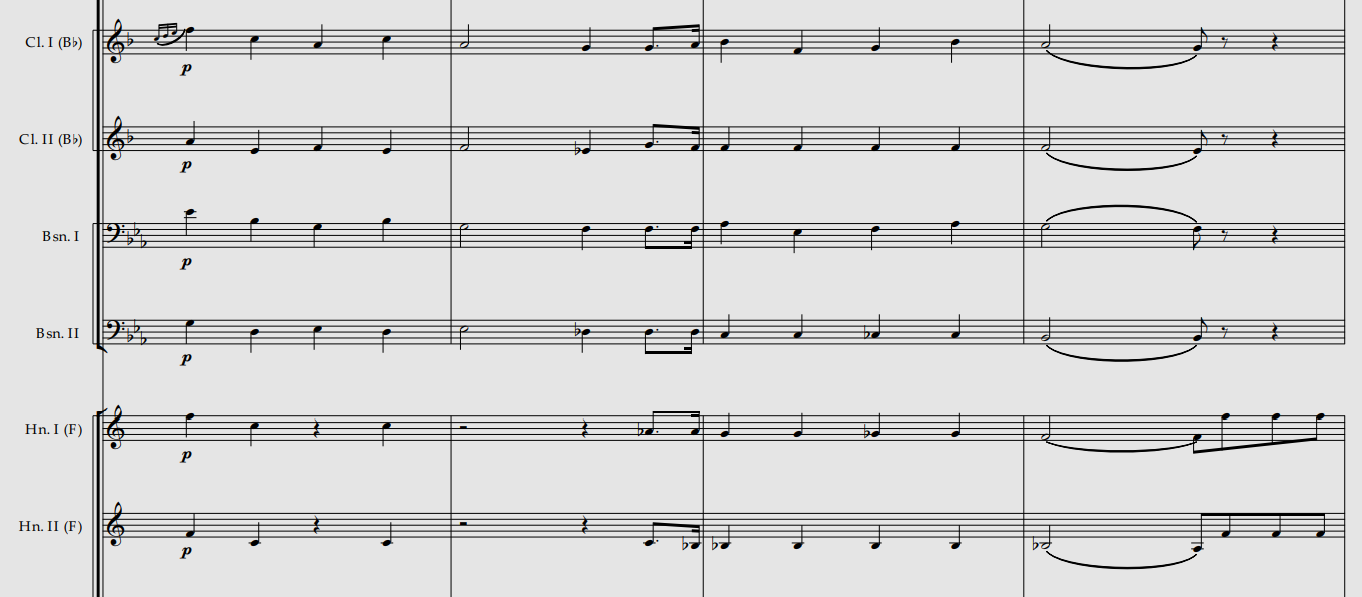

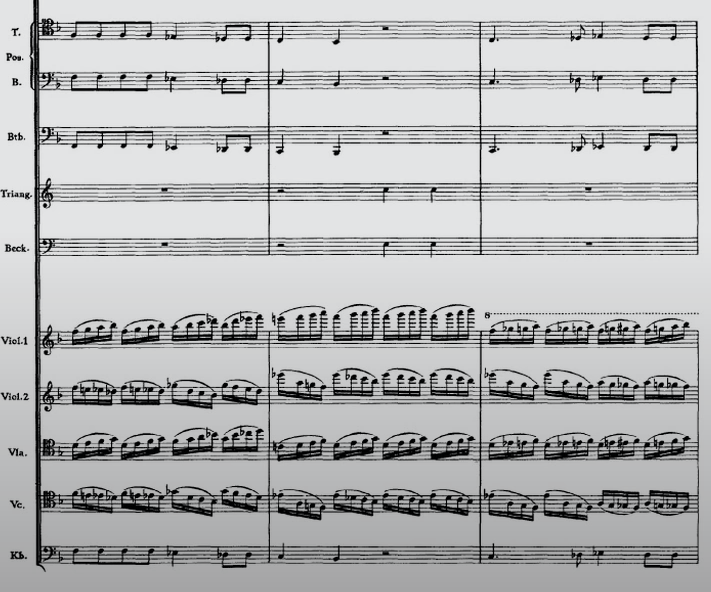

The introduction of the folk song Во поле береза стояла on solo oboe and bassoon.

The introduction of the folk song Во поле береза стояла on solo oboe and bassoon.When the theme repeats again after the first introduction, we see a textural change mainly in the embellishment line: running sixteenth notes are passed back and forth between the string section. The main theme is also doubled with more woodwinds.

The first repeat of the theme.

The first repeat of the theme.This textural development would continue for a few times:

Eventually, the theme is developed, first, by transposing the key(top) and then by rhythmic permutations (two in the middle). What we see before the recapitulation of the first theme of the 4th movement is now, after having gone through many developments, is just a melodic contour of the folk theme (bottom):

These permutations, as we will see in the following analysis of some of the music from the members of “The Mighty Five”, were not at all prevalent in other nationalistic Russian composers.

Tchaikovksy's Contemporaries

Mikhail Glinka was very influential in the development of “Russian classical music”. This development aimed to produce a distinct and national sound for Russian music. Notable followers are those such as the “Mighty Five”, which includes Balakirev, Cui, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Korsakov.

This school, as described by Tchaikovsky in his letter to Nadezhda von Meck in January 1878, due to their one-sided, lack of proper musical training, and biased admiration of one another, their music had suffered from lack of individuality. (letter 705)

This “lack of individuality”, as Tchaikovsky put it, highlights the difference between their composition styles and, in our case, how they develop simple melodies such as folk tunes.

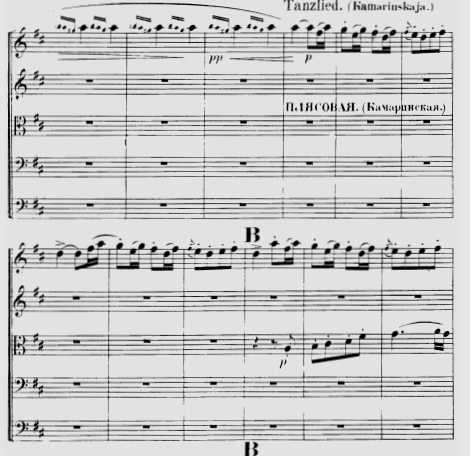

The music shares its name with a traditional style of Russian folk dance. And it was the first Russian orchestral work to be based entirely on Russian folk song. This music also served as one of the main inspirations for Tchaikovsky’s 2nd symphony, as it showed how folk songs can be used as symphonic materials. ( Warrack, Symphonies, pg. 17) One of Glinka’s composition Жизнь за царя(A Life for the Tsar) was also amongst one of his earliest musical impressions from his family’s orchestrion alongside Don Giovanni. (M. Tchaikovsky, pg. 23)

In previous examples of Tchaikovsky’s music, we see how he used harmony and melody to propel his music forward, creating tension and resolution. The themes inside Tchaikovsky’s music felt much more malleable; they seem to bend and adapt into their musical surroundings. On the contrary, Glinka’s music has a relatively more viscous implementation, most notoriously is how the ostinato in his 2nd theme stagnates the motivic development as it would break the character of the theme. Instead, the theme is repeated 75 times with textural developments happening in the background. (Brown, Final, 424)

The exposition of the 2nd theme..

The exposition of the 2nd theme..This theme would repeat several times with varying and colorful accompaniment.

However, several measures later, the theme remains in its same, unchanged form. And this repetition of the main theme can also be seen in the works of the composers from “The Mighty Five” as well.

Hundreds of measures later, the theme is still repeating itself in the same form.

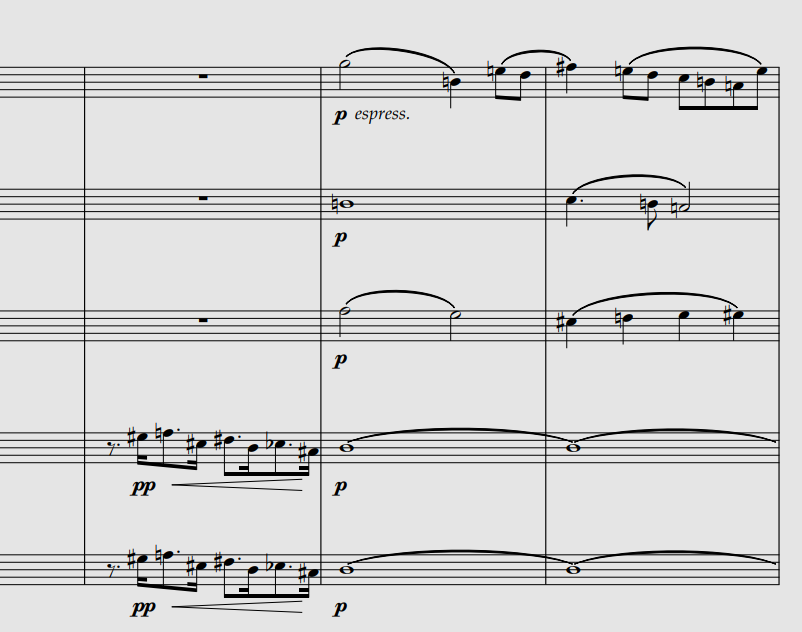

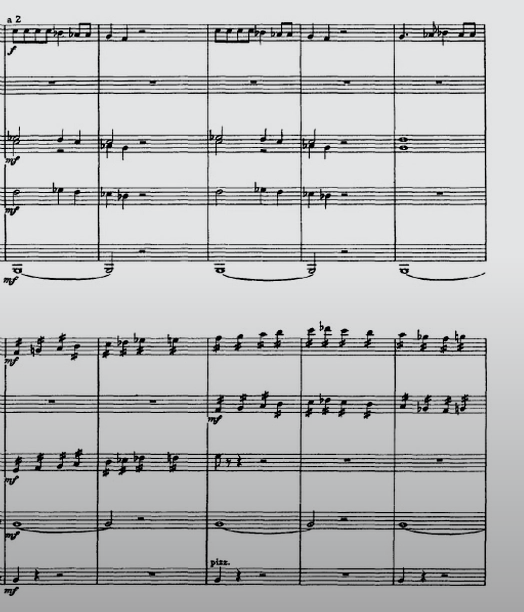

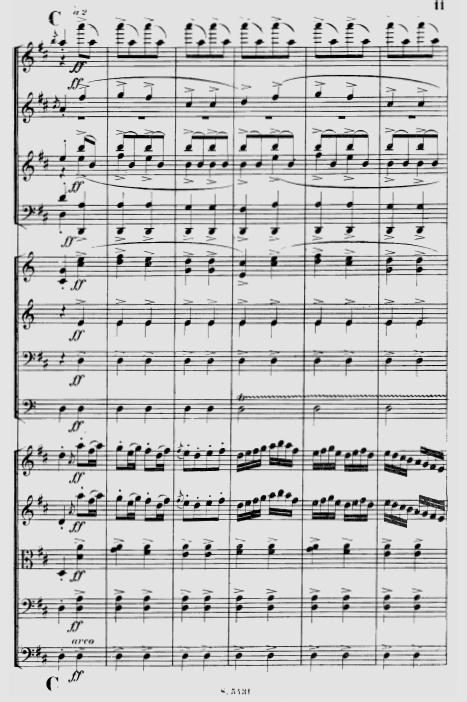

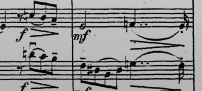

Hundreds of measures later, the theme is still repeating itself in the same form.Again, compare that repetition of theme with Tchaikovksy’s more western approach. Below are the middle theme from the second movement of his 6th symphony from two places, one directly from the exposition, and the other from around the ending of the theme. (B major)

Left: Violin I and Violin II; Right: Viola and Cello

Left: Violin I and Violin II; Right: Viola and CelloFolk Music

This section is an analysis of a few tunes from each of the countries Tchaikovsky had frequented from the year 1870 to 1878. The point of this section is not to prove that the music from those regions influenced Tchaikovsky’s music in any way, but to simply work out their musical structures and contours, so that they can be used in the arrangement process of the fictional concerto.

A lot of assumptions regarding the harmonic functions will be made, as all existing recordings are modern. It cannot be denied that the harmony employed by the performers in the aforementioned recordings are not affected by external musical influences that had no relationship with folk-music.

Folk cultures from the included regions are all rich and full of vitality; however, when dug deep enough, they show some shared inherent musical characteristics such as simple melody, modal harmony, harmonic minor scale, etc. So we will be cherry-picking tunes that are distinct enough in its structure/style to stand out amongst its peers.

Rule

- One tune that is known to have been incorporated into his compositions, and one more picked arbitrarily from that region’s repertoire.

Disclaimer

The existing notation of all the songs do not give a complete picture; this research is not a research about the history of folk music, but rather, analyses of “hypothetical” situations using some facts whose outputs are musical arrangements.

Because folk music are not harmonically complex, unless we see explicitly that all the notes in a bar belong to a certain chord outside of the one, two, four, or five chord, we will try to constrain our harmonic interpretation to only these four chords.

Ukraine

One of his favorite holiday spots was Davidov's estate (the estate of his sister’s husband), situated in Kamenka, Ukraine. He frequented this place from 1865 until his death in 1893, more than exceeded the goal he had set out in a letter to his sister in 1862:

“...to come to you for a whole year after my studies are finished to compose a great work in your surroundings.”

Many of his compositions were also composed in the pleasant settings of this estate, such as his String Quartet in B flat, the 2nd symphony, 2nd piano concerto, 1812, among others.

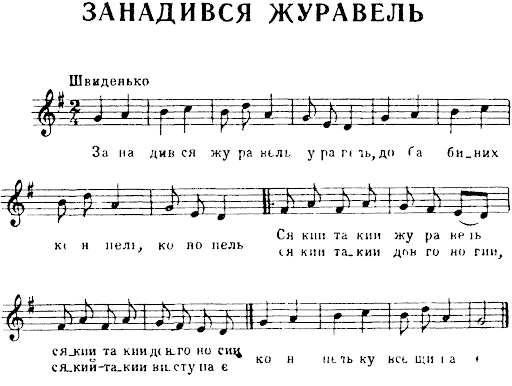

This one does not require many assumptions as we know for a fact that he used music from this Ukraine, also known as Little Russia, in his 2nd symphony, Little Russian. We’ll pick Журавель (The Crane), included in his 2nd symphony; and Ніч яка місячна (Moonlit Night), another famous Ukrainian folk song.

The harmony of these slavic folk songs can be inferred from their simple melodies, similar to western music. The tempo marking says швиденько or “quickly”.

Here, in the first two bars, we have the tonic, supertonic, mediant, and subdominant note, each can be assigned the most common chord progression for this type of pattern: I V I IV.

The third and fourth bar, it is apparent, as indicated by the intervals that the first beat of both bars are I chord, while the 2nd beat of both bars, we can safely generalize as V without breaking the harmonic functions.

In the B part (in the repeat sign), we can give each of the 4 measures V I V I respectively.

Ignoring the chord markings, this song, with its simple melody, is still easy to derive the underlying harmony thanks to the leading tone in the harmonic minor key.

We can also see that the note groupings are in groups of two: Am for 2 bars, E7 for 4, Dm for 2, and so on and so forth.

Other underlying details will be discussed in the Russian folk music section as the two are nearly, if not completely identical.

Conclusion for folk music from Ukraine:

Each note in the melodic line implies the underlying harmony.

Both the harmony and melody are simple.

Note groupings are even (2 bars, 2 notes, 4 bars etc., but never odd numbers).

Russia

There is a huge collection of folk songs from Russia used by Tchaikovsky, both directly (main subject of the music) and indirectly (used as a musical element).

We will pick one from his 50 Russian Folk Songs, and another, arguably the most iconic and popular themes. Well-known in Russia and many other countries: Коробе́йники (Korobeinki), also known as the Tetris theme.

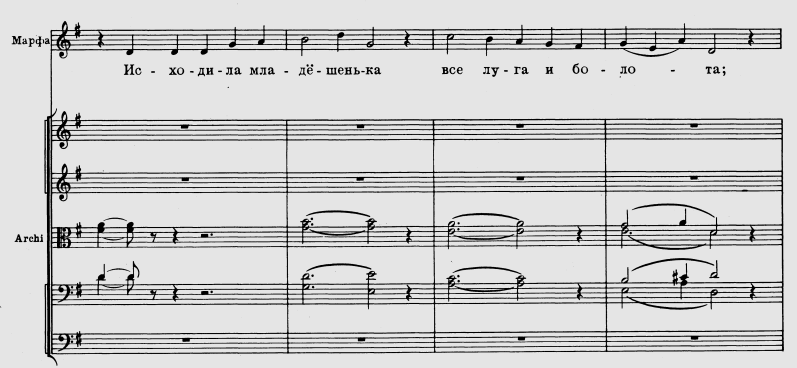

This song deserves special attention as it was incorporated into two other important Russian composers of the same school: Mussorgsky Исходила младёшенька from his opera Хованщина(left) and Korsakov Исходила младенька from his 100 Russian folk song collection(right).

Even though the texts and the harmonies in the two versions are somewhat different, we can still see that they share the same folk origin.

In both versions, we have the melody in 6/4 time signatures that are set to their own text. This fact is important as it is a common refrain in folk music adaptations of composers from the Russian school. As opposed to the freedom Tchaikovsky had shown in his works, composers from this school had the propensity to stick to the melodic contour of the original melody. In other words, the transcriptions aimed to be as accurate as possible as to not alter the text-music relationship of a song.

The 6/4 time signatures as opposed to Tchaikovksy’s ¾ (bottom) signature in his adaptation give therefore more freedom of expression when it comes to timing, which is more true to how folk music traditionally performed.

In Tchaikovsky’s adaptation, other than different harmonizations we have the aforementioned ¾ signature and most noticeable, fewer long notes. Some of the half notes from the first two versions are contracted into quarters.

Such changes can be found virtually anywhere in his 50 Russian folk songs. Why he did it, we can only speculate, but what this shows is his abstraction of text. As we have seen in the analysis section, this abstraction had surely helped some of the adaptations of these tunes in his works such as his symphonies stand out from the compositions of his contemporaries.

Tchaikovsky’s vacillation between different styles, even in a short period of time, is a sure impediment to us arriving at an unequivocal conclusion pertaining to his style. But, again, seeing how this research is part fact, part truth, we will just take this information as is.

This song by Nikolai Nekrasov, also known as Korobushka/Кoробушка, is arguably one of the most famous traditional Russian music thanks to it being used as the video game Tetris’s main theme.

Had the chord names not been notated, following the melodic contour of this song, we would have arrived at a similar, if not completely identical set of chord progressions.

Without crazy harmonizations like the ones given to the piece above by the three composers, the bare bones Russian folk music is not that complex. We can use western music theory to help us analyze -- confirm in this case -- the harmony of this music.

The A section consists of 2 4-bar phrases. Similar to slavic music from other regions such as from Ukraine, the melody is simple enough that we can see the underlying harmonic structure from the melody alone: the first two bars are basically just a broken 5 chord and the 5th and 6th bar consist of chord tones that are connected by passing tones. The chord between the mentioned 4 bars can also be deduced from the simple melody line: the 3rd and 4th bars are the chord tones of the tonic chord, connected by passing notes, while the last two bars are just chord tones. Referring to our western music theory, this indeed does not break our harmonic progression rules.

In the last 4 bars -- the B section -- we see similar patterns forming: chord tones with passing tones, broken chords in the melody, and just chord tones, from which we can be certain that similar harmony can also be applied here (the written chord is different, but that does not really concern us).

Conclusion for folk music from Ukraine:

The conclusion is the same as music from Ukraine: simple melodic/harmonic relationship where the melody controls the harmony with no motivic development.

The melodies are simple chord tones connected by passing notes in most cases.

Italy

A lot of his time, as can be seen from the location many of his letters were sent from, were spent in the congenial setting of Tuscany, most notably, Florence.

Unfortunately we do not know the exact folk tunes that inspired Tchaikovsky in this region, but we do know that he was infatuated with the local music, as evidenced by the following excerpt from his letter to Frau von Meck:

We will be looking at two tunes, one transcribed by Tchaikovsky in Pisa, and another random tune from the region.

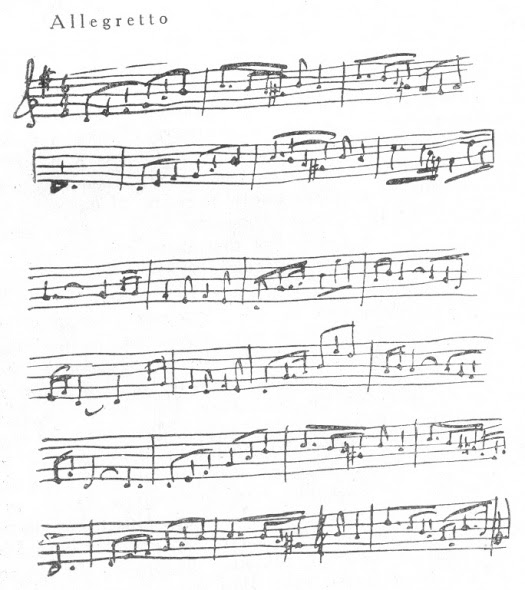

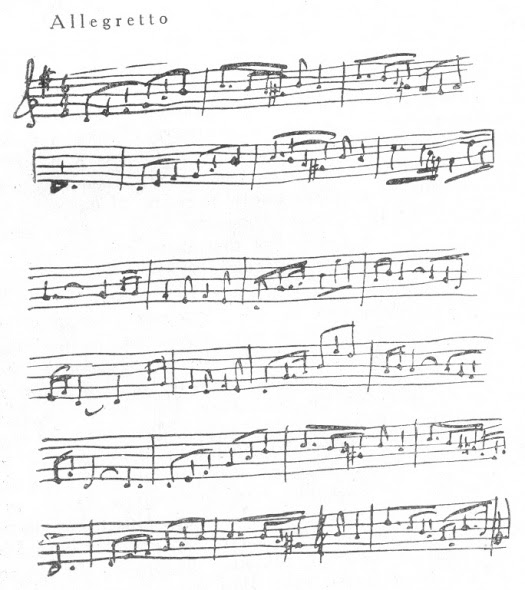

Tchaikovksy’s admiration for Italian folk music is mentioned several times in his letters. Though not mentioned explicitly nor is it known if this untitled song had inspired him to create any particular composition, the fact that he loved it so much he noted it down is a good enough justification for it to be included here.

The music for this type of dance was indeed characterized by fast (allegretto) and 6/8 time signatures. Judging from the tempo, the time signature, and the region this music was found, we will make an educated guess that this music possibly belongs to the Italian Tarantella folk dances.

It seems that this music, at least harmonically, is more complicated than Russian folk music. From the picture above, we see an A# which implies a secondary dominant, a V/IV in the key of G major. Other than that, the rest of the harmony and the structure appear to be equally simple.

The melody in both A and B sections are grouped in a 4-measure phrase with each 2nd repeat having different final measure. For example, the 4th measure, the end of the exposition of the first phrase ends with a dominant, implying a half cadence, while the 8th measure, the end of the repeat of the melody comprises mainly a sustained tonic, which of course, implies a perfect cadence.

Whether Tchaikovsky used this melody in his composition or not, we cannot know for certain, but one striking coincidence is the 2nd bar of this tune (left) and the 20th - 21st bar of this waltz from his third symphony (right).

Or the fact that the rhythm of the main motif of this waltz is similar to the 2nd bar and the similar ascending line preceding the waltz’s main theme and the 1st bar of the folk tune.

Tarantella’s popularity is evidenced in its widespread implementation, for example in Chopin’s Tarantella Op.43 and in the finale of Mendelssohn.

Originating sometime in the 17th century, Tarantella had seen itself being adopted throughout Italy like wildfire, replacing the name of many pre-existing Italian dance music.

Bear in mind that there are many types of Italian Tarantella dances, we will however be looking at only one from the lot: the Tarantella Napoletana, a Tarantella of Neapolitan origin.

Tarantella Napoletana, though itself is not a song, the name is often associated with this particular Italian Tarantella tune in the Tarantella Napoletana style. This tune is, like Korobushka, was popularized by various forms of media, be it music, TV shows, internet, etc. The first modern implementation of the tune is probably Buddy Arnold and Milton Berle’s “Lucky Lucky Lucky Me”, which also uses not only the dance rhythm, but the melody as well.

The melody is, like all other songs in this list, rather simple. Again, we won’t be following the notated chord but will infer simple chordal structure using western music theory.

The song is divided into 3 sections: A B C. With the exception of the first section, the melody of each section repeats itself 4 times. In section A, we can use the firs chord until the 3rd 2nd beat of the third bar and the first beat of the fourth bar, inferring from the notes, a four chord would be more appropriate. After that we go back again to the first chord in the fourth beat of the fourth bar and the first beat of the fifth bar.

Now, without having to go further, we see a pattern forming: all the heavy beats are chord tones, so most of these are just i iv and V except the C section which has a broken III chord in the melody.

Like folk music from Ukraine, is that when it comes to non-chord tones, there is a fixed shape and direction as to how a certain pattern is used. For example, this pattern will always be a non chord tone sandwiched between two chord tones, which is led into by a series of ascending or descending notes.

This fixed pattern that is prone to change in folk music is one of the reasons why we see stagnation in the musical development of music from the Mighty Five and Glinka. We can see that in such a strict and short environment, should anything be changed, it simply wouldn’t sound like the same song.

No motivic development.

Notes approaches are more sophisticated than the rest in this list.

Simple melody

A little more complex in terms of harmony.

Switzerland, Germany, Austria

Compared to Germany and Austria, Tchaikovsky did not stay in Switzerland as much, but it is important as it was here that the concerto was conceived.

There exists absolutely no evidence that he was inspired by folk music around Clarens. But Clarens was a small village in the mountains in the Vaud, bordering Geneva, where he spent a number of months in. We will speculate that he had come across at some point some music from that region.

From Yodelling to Ländler, the folk music from these alpine regions are nearly identical. We will be taking a look in this section at a Ländler and a waltz tune.

Popularized by the film The Sound of Music, Ländler is a folk-dance in ¾; a more unsophisticated cousin -- slower and without the accent on the second beat -- to waltz. Many classical had included this particular dance into their music, such as Schubert, Beethoven, Brucker, Mozart, etc.

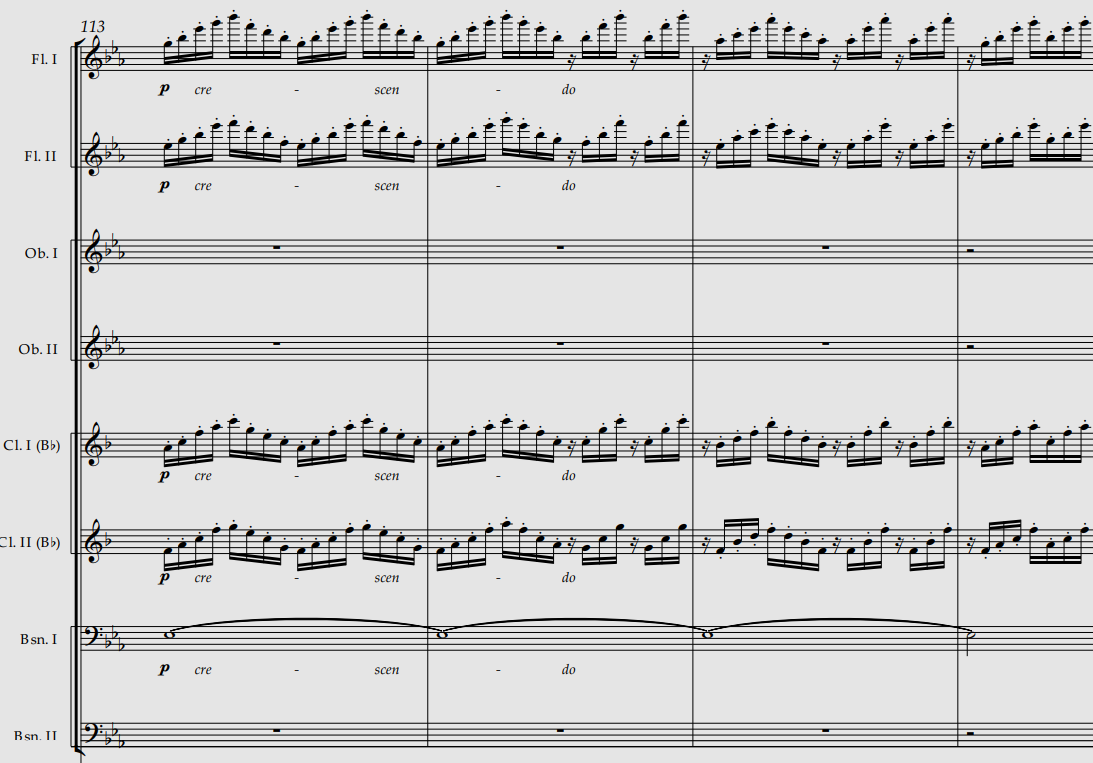

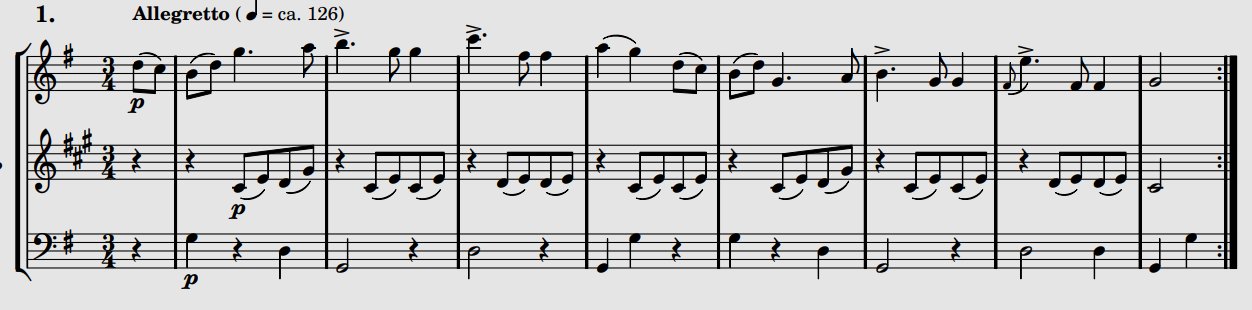

Reduction of the first theme from Neue Wiener for flute, Bb clarinet, and bassoon.

Reduction of the first theme from Neue Wiener for flute, Bb clarinet, and bassoon.This “Neue Wiener” by Joseph Lanner is maybe not the best example of folk Ländler as it borders on being a classical music itself, but it does help give us some ideas and help see some distinctions between itself and waltz.

While the tempo of Ländler is more akin to that of Minuet than waltz, due to them being more closely related, harmonically, Ländler relies heavily on I IV V chords and rarely deviates from this pattern. For example, in Beethoven’s 7 Ländler in D major, other than modulations, we don’t see any other chord being used at all other than I IV and V of their respective key.

Melodically, Ländler, and as we’ll see in a moment, its cousin Waltz is more like a collection of tunes/variations, so again, no motivic development.

There are chromatic approaches here and there, whether this really existed in older Ländler or not does not concern us, so we will assume that this is possible in all Ländler.

And unlike waltz, if we look at the first few bars, we see that Ländler, other than being slower, is more heavy on the first beat whereas waltz is more syncopated and feels less grounded thanks to its 2nd beat accentuation.

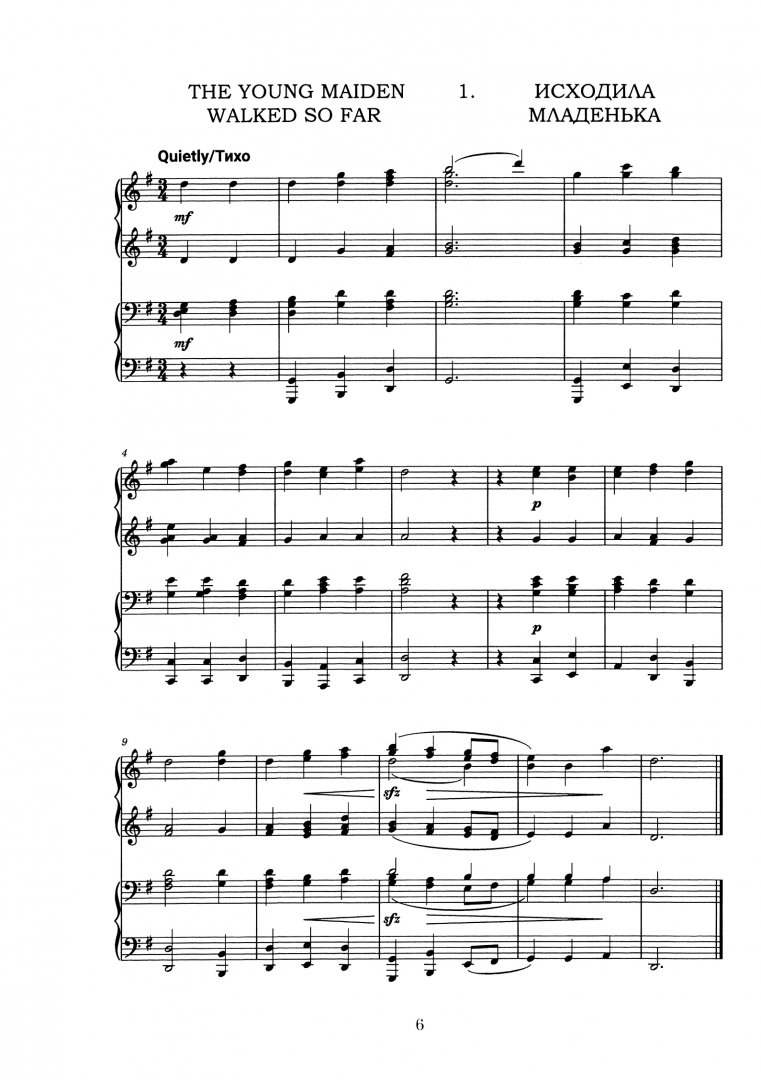

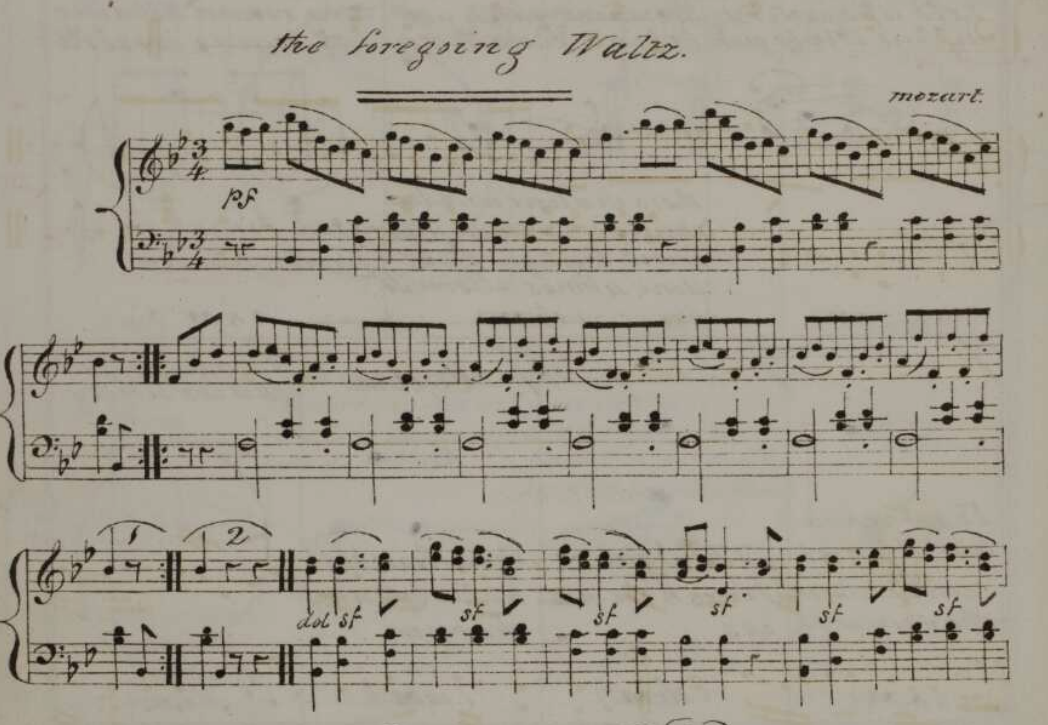

Even harder to separate from classical music is the waltz. Ever since its conception around the 13th century, waltz had seen itself spreading throughout Europe, picked up by various nations quickly. To ensure that we get the one closest to our folk music in terms of simplicity, in that it is not too musically complicated like most classical waltz, we will pick one from a book of almost 200 years in age.

This waltz tune from the 1826 TB Dance Book does not have much to say harmonically. It is exactly like Ländler. But what is intriguing now are the phrasings.

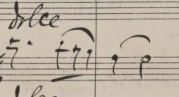

In the 2nd system, the articulation of the melody changes within the 2nd beat, from legato to staccato. In the 3rd system, we see explicit markings of sforzando on the 2nd beat, clearly indicating accents on the weakest beat.

This distinction, though slight, is a clear cut difference between Ländler and waltz, by having the accent on the weakest beat, the music becomes more free and less grounded, which is preferred when it comes to dance music and possibly why it became more popular. We see this phenomenon practically everywhere in modern music, be it jazz, rock, blues, dubstep, rock’n roll, pop, etc.

A lot of variations or many melodies in a single piece of music.

More sophisticated approaches using diatonic and chromatic.

Simple melody

Not much tension, most of the focus is on the rhythm.

Summary

Despite the similarities in some cases between music from each of the countries, be it in terms of meters, harmonic or melodic contour, there certainly are some musical traits that can be picked for use in this project. A good example would be the more indirect melodic approach of the Italian folk music (1st folk tune 2nd bar) and the more straightforward note approach of the slavic folk tunes. The information in the conclusion from each section will be used to help us arrange the concerto.